Okinawan "Te"

Chinese Tang Dynasty 681-907

Tote (Tang Hand/China Hand)

Japanese Samurai

Okinawan Bushi (GentlemenWarrior)

Okinawan Weapons (Kobuki)

Emporer Meiji (Mutsuhito Tennō)

1852 -1912

The Historical Migratory Influences of Martial Arts to the Ryukyu Islands and Okinawa

Introduction

The island of Okinawa, situated in the subtropical waters between Japan and China, stands as a crucible for the development and refinement of Ryukyuan martial arts. Its unique geography and history have rendered it a crossroads for cultural, political, and economic exchanges for centuries. The martial traditions that flourished here are not the result of simple invention, but of a complex migratory flow of ideas, techniques, and philosophies from neighboring lands and local roots. It is necessary to explore the historical migratory influences that shaped the martial arts of Okinawa, examining the blend of indigenous practices, Chinese innovations, Japanese interventions, and the broader currents of regional conflict and commerce to understand the significance of karate as a martial art.

Okinawa: An Island of Confluence

To understand the migratory influences on Okinawan martial arts, one must first recognize the island’s unique historical position. Okinawa was the heart of the Ryukyu Kingdom, an independent entity from the 13th to the 19th centuries, which served as a maritime hub between major Asian powers. Its location placed it along crucial sea routes connecting China, Japan, Korea, and Southeast Asia, and its rulers fostered diplomatic and trade relationships with all.

-

Ryukyu Kingdom’s Diplomatic Outreach: The Ryukyu Dynasty maintained tributary relations with the Chinese Ming and Qing courts (13th through the later part of the 19th centuries) , embraced trade with Japan, and interacted with Southeast Asian kingdoms. This openness facilitated the import of ideas, including martial philosophies and technologies.

-

Multicultural Influence: The Ryukyuan court employed envoys, translators, and merchants, many of whom returned with new knowledge, skills, and tools, including aspects of Chinese boxing and weaponry skills.

Indigenous Roots: The Ryukyuan Fighting Arts

While Okinawa’s martial arts are renowned for their cosmopolitan influences, their core is distinctly local. Centuries before formal karate emerged, indigenous fighting forms known as “Te” (meaning “hand”) existed among the island’s population. These systems were tailored for unarmed self-defense and local conflict deterrence. They were practiced through a method known as 'Tegumi" or intertwining hand, a form of indigenous wrestling.

-

Te: The Foundation: Practiced in secret and passed from generation to generation, Te reflected the necessities of Okinawan society, focusing on close-quarters combat and personal protection.

-

Village Variations: Each Castle Village—Shuri, Naha, Tomari—developed its own variant of empty hand, adapted to local culture, and needs, setting the stage for later diversification of karate influences.

Influence from China: The Flow of Techniques and Philosophy

The most significant migratory influence on Okinawan martial arts arrived from China. Beginning in the 14th century, Chinese envoys, merchants, and immigrants brought philosophical and practical knowledge of Chinese martial arts—especially forms of Chuan Fa (Kenpo).

-

Chinese Envoys, Diplomats and Immigrants: Diplomatic missions and merchant exchanges led to the settlement of Chinese families and individuals in Okinawa, particularly in the Kumemura district. These migrants (known as the 36 families landing in 1392) practiced and taught Chinese methods of self-defense and combat.

-

Study Abroad: Okinawan Nobles such as Kanga Sakugawa and (most notably Sokon "Bushi' Matsumura) traveled to Fujian province, among other regions, to learn Chinese styles directly, bringing back techniques such as the “White Crane” , "Five Animals" and “Five Ancestors” arts, which influenced local practice.

-

Integration into Te: The blending of Te with Chuan Fa created new hybrid systems, emphasizing circular movements, breath control, and internal energy, hallmarks of classical Chinese martial arts which was called ToTe or "China Hand). Martial arts were reserved to the realm of the noble class or Shizoku (those having Royal Genealogy). The Woji, Aji,(princes),Oyakata , Pechin, Uhugushuku (Bushi) classes (Satonushi-land holders) controlled the fiefdom of the Ryukyu Kingdom. Sokon Matsumura, being appointed by King Sho Tai as the Kings personal Royal body guard (Bucho) and given the title of "Bushi" (Gentlemen Warrior) and oversaw the training of the Uhugushku Class, (Castle Warriors) which had a direct influence in their development.

-

Philosophical Exchange: Beyond technique, according to Choki Motobu, the martial arts had no influence from Chinese thought—including Confucian, Taoist, and Buddhist philosophies. The code of the Bushido filtered into the ethical and spiritual underpinnings of Okinawan martial arts, shaping ideas about discipline, self-improvement, compassion and non-aggression.

Japanese Subjugation and the Revocation of Weapons

The late in the 14th century by King Sho proclaimed the confiscation of all weapons and prohibited their possession by subjects of the king, essentially to stave off any uprisings after the unification of the three kingdoms. Early in the 17th century Japanese Samurai brought a dramatic shift to Okinawa’s martial culture. After the Satsuma clan of Samurai, provincially controlled by the Shimazu Family in southern Japan invaded and subjugated the Ryukyu Kingdom in 1609, the social and political landscape changed.

-

Ban on Weapons: Satsuma authorities imposed strict controls, prohibiting the possession of firearms and bladed weapons among the local population. This revocation intensified the focus on unarmed combat and the development of improvised weapon techniques using farming tools (the origin of Okinawa kobuki which are defensive weapons).

-

Japanese Influence: Over time, Japanese samurai culture and martial values permeated Okinawa, introducing new elements of etiquette, hierarchy, and training methodology.

-

Secret Practice: The suppression of weapons and the anxiety of foreign rule forced martial arts practitioners to train in secrecy, further refining their systems and fostering innovation.

Currents of Trade and Cultural Exchange

Aside from overt migration and conquest, the ongoing flow of trade contributed to the evolution of Okinawan martial arts. Merchants from China, Korea, and Southeast Asia brought goods and knowledge, and in the process, their own approaches to self-defense and weaponry.

-

Maritime Traders: As seaborne traders passed through Okinawa, local martial artists had opportunities to observe and adopt techniques seen in other cultures, creating a melting pot of martial traditions.

-

Cross-Pollination: The adaptive nature of Okinawan martial arts is reflected in their openness to new ideas and willingness to integrate skills from diverse sources, whether through observation, formal study, or friendly exchange.

Exportation and Redefining the Art of Tote

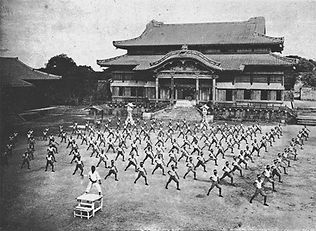

Meiji Restoration (1868-1912)

On 3 January 1868, Emperor Meiji declared political power to be restored to the Imperial House. The goals of the restored government were expressed by the new emperor in the Charter Oath. By the 1870s, the Emperor's authority was unquestioned. The new government reorganized whole strata of society, abolishing the old currency, the domain system, and eventually the class position of the samurai. The abolition of the shogunate and the introduction of industrialization of society emulating the foreign imperial powers of colonization led to the ultimate end of feudalism in Japanese society and the practice of sakoku (national isolationism). The Uhugushuku "Bushi" Class as well as the Royal King Sho and his nobility were stripped of title and status and became common subjects of the Ryukyu prefecture.

-

The Castle warriors (formal forbidden from) had to find work as farmers or fishermen or teach their trade to the local villagers to earn an existence.

-

The introduction of Tote (Empty Hand) was promoted by Anko Itosu to the prefectural school system as a means of physical education devoid of the lethality and use of weapons.

-

Exportation of Tote to Japan in 1919 by Gichin Funakoshi, Choki Motbu, Kenwa Mebuni, Chomo Hanashiro and others.

-

Secret pact by the Okinawan masters of (kakushite), to show but not teach the art of Okinawan Tote left the Japanese with a truly empty art.

-

Because the Japanese already had Jujutsu and Aikijutsu and Kenjutsu their interests did not lie with the so called grappling arts.

-

University students lacking the true application of the katas taught by Funakoshi, reversed engineered the meanings of the movements using Kenjutsu as a template. Many of the high and flashy kicks were introduced by Gigo Funakoshi (Gichin's son), from French Savate fighting.

-

The artificailly exagerated Maai (combat distance) was a result from teh kenjutsu model and applied to the punch/block /kick stylization of Japanese sport karate.

-

The metamorphosis of the close quarters combat art of Tote into a competition sporting activity of Japanese karate has expanded an interest in the art world wide, but it lacked the lethality associated with its original art.

-

1935 the Japanese influenced Gichin Funakoshi and other Okinawan Masters to changing the ideogram of "Tang" (To) from their Okinawan Martial art to "Kara" in order to appease the Japanese Imperialistic government of the time, thus removing any association with its Chinese origins.

-

In 1945, after fall of the Imperail Japanese to the U.S. and its allies during WWII, the American occupation of Japan saw an exportation of Japanese Sport Karate to the U.S. by G.I's (U.S. Servicemen) when returning after 1 or 2 years of exposure in Japan.

-

The idea that an foreign occupying military force would be taught the secrets of an ancient fighting art native to the subjugated people was treated in the same way the Okinawans saw the Japanese Satsuma Samurai in 1609, and kept the true art hidden in plain sight.